| It all started in Edinburgh, before we had even set off for Australia. “It’s not pronounced Kos-i-us-co, it’s Kosh-zhis-kŏ: three syllables, not four”. Micha’s eyes lit up as she continued, “Koshisko was from Poland – he was an ancestor of mine!” This unlikely revelation came from the mother of the family that had agreed to take teenager James into their bosom for the three weeks that Sarah and I had booked ‘down under’. When we explained to Micha the main reason for our trip - to climb Mt Kosciuszko, the highest mountain in Australia - she enlightened us about her ancestor of the same name: a Polish freedom fighter who lived from 1746 to 1817, fought in the American Revolutionary war, led Poland's last struggle for independence against Russia, and eventually became a citizen of the United States.

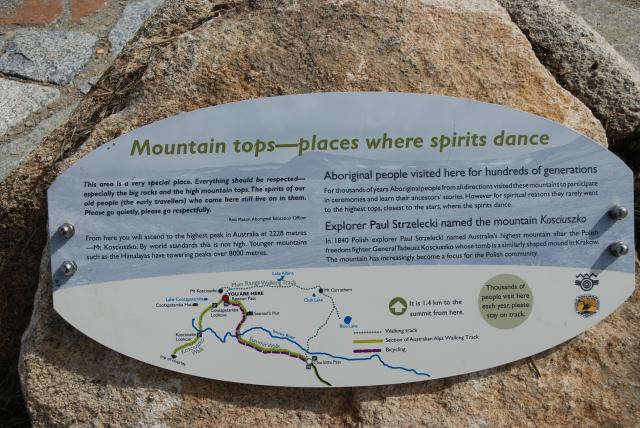

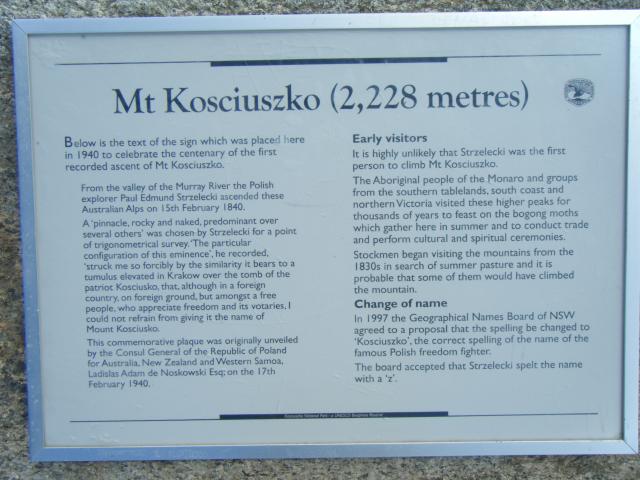

The peak was christened in 1840 by a Polish-Australian explorer called Paul Strzelecki. He named it Kosciusko because it reminded him of the eponymous Mound in Krakow – an artificial hill 34 metres tall, constructed to commemorate the Polish national hero. Whilst exploring this corner of Australia, Strzelecki wrote: “The particular configuration of this eminence struck me so forcibly by the similarity it bears to the tumulus elevated in Krakow over the tomb of the patriot Kosciusko that, although in a foreign country, in foreign ground, but amongst a free people who appreciate freedom and its votaries, I could not refrain from giving it the name of Mount Kosciusko.”

Thus this corner of a foreign field is forever associated with Poland, a little known fact that explains why so many Polish visitors are attracted to the area today.

In reality Australia’s highest mountain turned out to be much less shapely that its Krakow counterpart and I wonder whether Strzelecki might not have confused it with the continent’s second highest peak - Mount Townsend - when he wrote about... “A pinnacle, rocky and naked, predominant over several others”. Just before closing this history lesson, I should add a footnote on the mountain’s spelling. Proponents of political correctness have campaigned to add a ‘z’ to the name, asserting that Kosciuszko is a more accurate reflection of the Polish spelling. However, to most Aussies none of this pedantry matters a jot: to them, Australia’s highest mountain is simply and affectionately nicknamed ‘Kozzy’!

Exponents of seven summiteering differ in their view as to what constitutes the seventh continent. To some, it’s Oceania, making the highest peak ‘Carstenz Pyramid’ (Puncak Jaya) in Papua New Guinea: over twice the height of Kosciusko at 4884 metres. To others it’s Australia, which makes Kozzy the baby of the seven by a long way, at only 2228m. But this relativity is only an accident of geology and time. Unlike brash new landscapes like the Himalayas, Andes and New Zealand Alps, where some mountains are gradually increasing in height through colossal tectonic forces, the Australian Alps have been steadily eroded by millions of years of ice, wind and rain to become mere shadows of their former self. This, then, is a truly ancient landscape, a timeless 'dreamtime' landscape which - like so many other high places in the world - seems more real than reality itself.

|

This means that climbing Kosciuszko is a trek rather than an expedition: you can complete it comfortably in a shortish day, although in an effort to appear a bit more gnarly some seven summiteers sex up their experience by doing it when the Snowy Mountains are actually snowy, adding another photo to their collection of white summits. As for Sarah and me, we were quite content to do the trek in February - the tail end of summer in the southern hemisphere and not a vestige of snow in sight.

Kosciuszko mountain retreat lies just within the eponymous National Park in New South Wales. This place consists of seven thousand square kilometres of rugged mountains and fragile alpine wilderness. Having arrived at the camp ground late and in the dark, we were totally unprepared for the spectacle that greeted us the next morning: several wild kangaroos happily hopping about beneath the gum trees. There was absolutely no doubt about which continent we were on now.

|

Thoughts of breakfast were pushed aside in a frenzied photofest. But later - when hunger eventually overtook us - the Joeys seemed perfectly content to queue up for a campervan breakfast which eventually ended in an undignified tussle for the cornflakes (the Kangaroos won). Somehow our stereotypical view of large, timid creatures in the outback had to adjust to accommodate their smaller, mountain-dwelling relatives, busily bouncing about the Great Dividing Range and cheekily consuming their continental breakfast with a couple of crazy Pommies.

The short drive by campervan to the Kosciusko trailhead passes through Perisher, a purpose-built ski village within the largest snow resort in the southern hemisphere (it’s difficult not to think of it as Perishing in winter – which it probably is). Like all purpose-built ski villages that are vibrant and pulsating during the season, Perisher appeared rather incongruous and forlorn in the Australian summer sunshine, but it did produce two startlingly unexpected revelations for us.

|

The first was the best BLT in the Universe. The second – and you’re not going to believe this - was an underground railway station. No, I’m not joking: there’s an eight kilometre train track tunnelled into the mountains here (maximum incline 12.5%, maximum depth 550m) to enable skiers to reach otherwise inaccessible slopes. I’m not talking about a funicular railway to get you up to the high pistes. No, this is effectively an underground system in the middle of a National Park wilderness in the flattest and smallest of the earth’s seven continents. In one’s relentless quest for the seven summits, it doesn’t get much stranger than that …

The tarmac road runs out at Charlotte (or Charlotte’s) Pass (1,837 metres above sea level). Charlotte Adams was the first European woman to climb Mount Kosciuszko, back in 1881. Although there is no recorded account of the very first European ascent, stockmen undoubtedly roamed the area from the 1830s onwards in search of summer pastures and for thousands of years before that it is certain that Aboriginal peoples knew this mountain range.

Indeed according to Aboriginal oral tradition, Kosciusko has a special spiritual significance. For thousands of years Aborigines from all directions visited these mountains to participate in ceremonies, learn from their ancestors’ stories and feast on the bogong moths which congregate here in summer. However, for reasons of spiritual deference, these seasonal guests rarely went to the highest tops, closest to the stars, where their ancestral spirits are believed to dance.

Photo: Puls Polonii |

From Charlotte’s Pass it’s an easy five mile walk up to the top of Australia, for this was once a driveable dirt road. There are interpretive panels showing old cars toiling up to Rawson’s Pass, not far from the summit, but because of overuse, vehicles were banned in 1976, since when the road has been a walking track. That explains why it’s such a pleasure to hike here: the skilful Aussie engineers constructed an easy gradient that threads gently up through the snow gum tree line, winding around the contours and becoming part of the landscape rather than fighting it.

After leaving the last of the stunted snow gums behind, you enter the alpine zone. As you might expect, these alpine areas are rare indeed in Australia: within the Kosciusko National Park there are only 250 square kilometres of the stuff (a mere 4% of the Park area) and it drops to around 1% around Mt Kosciusko itself. This ecosystem is a windswept patchwork quilt of alpine heaths, herbfields, bogs and fens which must have been tiresome indeed to traverse before 1090 when the road was constructed. But ours was a gentle gravel surface with plenty of hidden culverts to keep the surface dry and numerous weather-beaten snow poles to show the route in winter.

In fact our biggest concern during the three hour ascent was not the ground conditions but the notorious Australian sunshine: without proper protection you can quickly fry in these ozone-challenged conditions. But the mountain gods were smiling on us that day and we were lucky in many respects. For a week beforehand there had been unseasonably heavy rain that had thwarted all but the most committed of climbers, whereas our summit day was characterised by light clouds, sunshine and good visibility.

|

Two thirds of the way up sits the first of two structures on the route - Seaman’s Hut - built by the New South Wales tourist bureau in 1929 following a mountaineering tragedy. This survival shelter is a memorial to Laurie Seaman who, along with another climbing companion, died whilst descending Kosciusko on 13th August 1928. Lest one underestimate the power of this or indeed any other mountain, Seaman’s Hut contains another memorial commemorating the lives of four young snowboarders who died of exposure near here on 7th August 1999.

At Rawson’s Pass (2100m) our track was joined by another, shorter route to the summit: a four mile mesh walkway accessed by a chairlift ride from the ski resort of Thredbo. This route has proved so popular by the estimated 100,000 or so people who now visit the mountain each summer that it required the construction of Australia’s highest public conveniences in 2007 (and yes, we did!). After the peace and quiet of our gentle ascent from Charlotte’s Pass we were now painfully aware of chattering young Japanese tourists and older intrepid Australian trekkers. The surprise to us was a seeming lack of younger Australian hikers. ‘Did young Aussies not get out into the mountains’ we wondered? ‘Perhaps they were off on less popular routes?’

As the last hundred metres of path circled around towards the top of the continent it revealed views of the Great Dividing Range: long ridges, deep valleys and distant blue horizons. And then the vista became a whole 360 degree panorama as the 2,228 metres (7,310 ft) summit cairn of Kosciusco came into view.

We waited patiently for the chattering groups of tourists to depart this hallowed ground so sacred to the Aboriginal people - and now sacred to me as the sixth and penultimate summit of my global adventure. Finally, it happened. The cameras stopped clicking, the throng dispersed and peace broke out on top of Mt Kosciusco. We had reached the highest point in Australia, closest to the stars, where the ancestral spirits of the Aboriginal people danced. We resisted the temptation to dance ourselves and instead we reflected, communing for a while with the spirits of the Snowy Mountains…

In David Horton’s Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Australia (1994) there is a wonderful quote: People come and go, but the Land, and stories about the Land, stay. This is a wisdom that takes lifetimes of listening, observing and experiencing.... There is a deep understanding of human nature and the environment... sites hold 'feelings' which can not be described in physical terms...

In the summit silence it was almost possible to capture the hint of an echo of those feelings. Perhaps one day we too could come to experience a deeper dreamtime understanding.

Finally, the time to descend approached. The last word belongs to some Aboriginal advice to be found on a plaque at Rawson’s Pass: “Everything should be respected – especially the big rocks and the high mountain tops. The spirits of our old people (the early travellers) who came here still live on in them. Please go quietly, please go respectfully”.

Not a bad creed for all those who love the mountains.

James Ogilvie

Social & Planning Policy Advisor

Forestry Commission Scotland

james.ogilvie@forestry.gsi.gov.uk |